Introduction

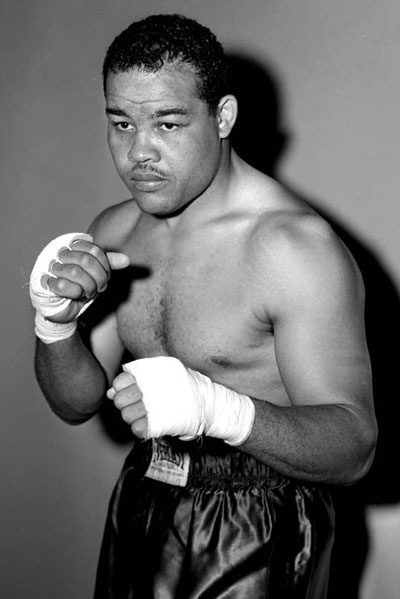

Many great African-American athletes contributed to Civil Rights, such as Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige for baseball, and the team, Harlem Globetrotters, for basketball. However, as Joe Louis' domination of boxing ended, professional sports in American moved toward integration of races. Boxing was ahead of the other sports in affording African-Americans opportunity to participate at its highest levels. Joe Louis stepped in to the professional boxing scene in 1934 with great talent. He was known as the "Brown Bomber". In the beginning of his career, he defeated many outstanding heavyweight fighters such as Stanley Poreda, Natie Brown, and Rosco Toles. (Mead,1985)

"Race Man"

During Joe Louis' boxing career he was given the label as a "Race Man", a man of high distinction who showed racial progress and leadership. Louis was heavily covered by both black and white press and both gave different views when describing Louis before facing former champion Primo Carnera in June 1935. The white press were skeptical on if he could "handle fighting against boxings big men". The black press believed Louis would win easily, which he proved correct. According to Runstedtler (2005), following Louis' victory over Max Baer in September 1935, "four centuries of oppression, of frustrated hopes, of black bitterness" rose to the surface. "Louis was a consciously felt symbol.....the concentrated essense of black triumph over white." Joe's manager Roxborough gave him specific instructions to never be photographed with a white woman, never to gloat over an opponent, never to participate in a fixed fight, to fight and live clean. These directions were given in order to shape Louis' image within white America and inspired by former black boxer Jack Johnson. (Renick & Rosen, 2010)

Important Events

The Battle of the Century - "Brown Bomber" vs "The Black Uhlan of the Rhine"

His meeting with German Max Schmeling, who was called "The Black Uhlan of the Rhine", on June 19, 1936, gave Louis the first and most painful defeat of his boxing career. Schmeling's nickname was referenced to the German lance-armed light cavalry unit. However, on June 22, 1938, Louis won the rematch with Schmeling by a decisive first round knockout. America celebrated this victory as news was increasing of the Nazi's persecution of the Jews. It was a meaningful victory for Louis himself and for his country, also at the same time he struck a hurtful blow to Hitler and Nazi Germany. It wasn't until Joe Louis defeated German boxer Max Schmeling, shattering Hitler's racist theories, that an African American was truly admired and embraced as America's world champion by a majority of Americans. (Mead, 1985)

His meeting with German Max Schmeling, who was called "The Black Uhlan of the Rhine", on June 19, 1936, gave Louis the first and most painful defeat of his boxing career. Schmeling's nickname was referenced to the German lance-armed light cavalry unit. However, on June 22, 1938, Louis won the rematch with Schmeling by a decisive first round knockout. America celebrated this victory as news was increasing of the Nazi's persecution of the Jews. It was a meaningful victory for Louis himself and for his country, also at the same time he struck a hurtful blow to Hitler and Nazi Germany. It wasn't until Joe Louis defeated German boxer Max Schmeling, shattering Hitler's racist theories, that an African American was truly admired and embraced as America's world champion by a majority of Americans. (Mead, 1985)Although the two champions met to create a remarkable game, the two fights represented the broader political and social conflicts of the times. As the first significant African American athlete since Jack Johnson, Louis was among the few focal points for African American pride in the 1930s. Moreover, as a competition between representatives of the United States and Nazi Germany during the 1930s, the fights came to indicate the struggle between democracy and dictatorship. From his great performance in the match, he was elevated to the status of the first true African American national hero in the United States.

He entered as a private, and left with rank of sergeant. As a sergeant during World War II, Louis mostly fought exhibition matches to entertain the troops and raise funds. He ended up donating around $100,000 to armed forces relief efforts. Louis fought a charity bout for the Navy Relief Society against his former opponent Buddy Baer on January 9, 1942, which generated $47,000 for the fund. Another military charity bout on March 27, 1942, (against another former opponent, Abe Simon) netted $36,146. Before the fight, Louis had spoken at a Relief Fund dinner, saying of the war effort: "We'll win, 'cause we're on God's side.” The media widely reported the comment, instigating a surge of popularity for Louis. Slowly, the press would begin to eliminate its stereotypical racial references when covering Louis, and instead treat him as an unqualified sports hero.

He entered as a private, and left with rank of sergeant. As a sergeant during World War II, Louis mostly fought exhibition matches to entertain the troops and raise funds. He ended up donating around $100,000 to armed forces relief efforts. Louis fought a charity bout for the Navy Relief Society against his former opponent Buddy Baer on January 9, 1942, which generated $47,000 for the fund. Another military charity bout on March 27, 1942, (against another former opponent, Abe Simon) netted $36,146. Before the fight, Louis had spoken at a Relief Fund dinner, saying of the war effort: "We'll win, 'cause we're on God's side.” The media widely reported the comment, instigating a surge of popularity for Louis. Slowly, the press would begin to eliminate its stereotypical racial references when covering Louis, and instead treat him as an unqualified sports hero.

Louis' Military Service - WW II

He entered as a private, and left with rank of sergeant. As a sergeant during World War II, Louis mostly fought exhibition matches to entertain the troops and raise funds. He ended up donating around $100,000 to armed forces relief efforts. Louis fought a charity bout for the Navy Relief Society against his former opponent Buddy Baer on January 9, 1942, which generated $47,000 for the fund. Another military charity bout on March 27, 1942, (against another former opponent, Abe Simon) netted $36,146. Before the fight, Louis had spoken at a Relief Fund dinner, saying of the war effort: "We'll win, 'cause we're on God's side.” The media widely reported the comment, instigating a surge of popularity for Louis. Slowly, the press would begin to eliminate its stereotypical racial references when covering Louis, and instead treat him as an unqualified sports hero.

He entered as a private, and left with rank of sergeant. As a sergeant during World War II, Louis mostly fought exhibition matches to entertain the troops and raise funds. He ended up donating around $100,000 to armed forces relief efforts. Louis fought a charity bout for the Navy Relief Society against his former opponent Buddy Baer on January 9, 1942, which generated $47,000 for the fund. Another military charity bout on March 27, 1942, (against another former opponent, Abe Simon) netted $36,146. Before the fight, Louis had spoken at a Relief Fund dinner, saying of the war effort: "We'll win, 'cause we're on God's side.” The media widely reported the comment, instigating a surge of popularity for Louis. Slowly, the press would begin to eliminate its stereotypical racial references when covering Louis, and instead treat him as an unqualified sports hero. Accordingly, Louis used his personal connection to help the cause of various black soldiers with whom he came in to contact.

Louis was the focus of a media recruitment campaign encouraging African-American men to enlist in the Armed Services, despite the military's racial segregation. When asked about his decision to enter the racially-segregated U.S. Army, Louis' explanation was simple: "Lots of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain't going to fix them."

Joe Louis' legacy is that he overcome barriers and created a precedent to allow black athletes to compete in all sports in America. (Renick & Rosin, 2010) "he encouraged others to confront the limits of segregation and discrimination, though today he is often compared less to Ali and Johnson." (Renick & Rosen, 2010) Joe retired from boxing March 1, 1949, and unfortunately was extremely in debt during his later years in life.

Joe Louis' legacy is that he overcome barriers and created a precedent to allow black athletes to compete in all sports in America. (Renick & Rosin, 2010) "he encouraged others to confront the limits of segregation and discrimination, though today he is often compared less to Ali and Johnson." (Renick & Rosen, 2010) Joe retired from boxing March 1, 1949, and unfortunately was extremely in debt during his later years in life.Reference

Bal, Richard. (1996). Joe Louis: The Great Black Hope. Dallas: Taylor Publishers.

Barrow, Joe Louis, Jr., and Barbara Munder. (1988). Joe Louis: 50 Years an American Hero. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mead, Chris. (1985) Champion - Joe Louis, Black Hero in White America. New York: Scribner, 1985.

Margolick, D. (2005). Beyond Glory. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Renick, C. O. & Rosen, J.N. (2010). Fame to Infamity. Jackson: University Press of Mississipi.

Runstedler, T. E. (2005). Race, Identity and Sports in the Twentieth Centurty in The Game. New York: Palgrace Macmillan.

Retrieved November 7, 2011 from http://www.notablebiographies.com/Lo-Ma/LouisJoe.html

Retrieved November 7, 2011 from http://coxscorner.tripod.com/alilouis.html

Retrieved November 7, 2011 from http://www.boxinginsider.com/history/joe-louis-as-civil-rights-pioneer/

Retrieved November 7, 2011 from Nazi&Joe: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US-Israel/louis.html